Saturday, July 31, 2021

Monday, July 26, 2021

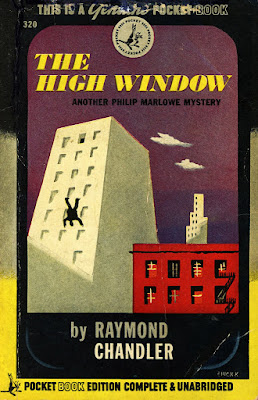

raymond chandler, poet

Dead men are heavier than broken hearts.

It seemed like a nice neighborhood to have bad habits in.

I been shaking two nickels together for a month, trying to get them to mate.

It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.

She gave me a smile I could feel in my hip pocket.

The coffee shop smell was strong enough to build a garage on.

She had eyes like strange sins.

Until you guys own your own souls you don’t own mine.

I looked back at Breeze. He was about as excited as a hole in the wall.

I’m all done with hating you. It’s all washed out of me. I hate people hard, but I don’t hate them very long.

She looked playful and eager, but not quite sure of herself, like a new kitten in a house where they don’t care much about kittens.

“I don’t like your manner,” Kingsley said in a voice you could have cracked a Brazil nut on.

She smelled the way the Taj Mahal looks by moonlight.

Leave us do the thinking, sweetheart. It takes equipment.

California, the department-store state. The most of everything and the best of nothing.

I was as hollow and empty as the spaces between stars.

The French have a phrase for it. The bastards have a phrase for everything and they are always right. To say goodbye is to die a little.

I belonged in Idle Valley like a pearl onion on a banana split.

I’m not a young man. I’m old, tired and full of no coffee.

Guns never settle anything, I said. They are just a fast curtain to a bad second act.

Don’t kid yourself. You’re a dirty low-down detective. Kiss me.

Thursday, July 15, 2021

diane tucker | three poems from 'nostalgia for moving parts'

Tuesday, July 06, 2021

when did richard allen go to the movies?

Monday, July 05, 2021

gilette elvgren | andy & reggie

St. Ives, a carbuncle on Cornwall’s boot,

Where, two years ago, walking the commercial drag,

The smell of lamb Pasties,

Fudge slavered with Cornish clotted cream,

Galleries with an endless parade of seascapes,

The half moon harbor, tide out, boats cantered,

We happened by a small, old, Methodist Church.

Wedding music wafted onto Fore Street.

Passersby couldn't care less,

Inside the groom, tuxedo, bent over,

Was being married to a flaxen haired beauty,

Striking in her white dress and lace.

The bridegroom levered by two of his male entourage,

Could hardly say, “I do”.

They sat at a table, as if agreeing to a contract,

The bride had no one to throw the flowers to.

A song, then it was over, no kiss exchanged.

And as I wondered how and why,

Beauty and the broken beast made their way,

Toward the store front entrance to the chapel.

In the narrow cobbled street outside sat the limousine,

Motor running, tourists gliding by on either side.

Reggie and Andy, for that was their names,

Emerged. No rice.

Reggie, in the later grip of muscular dystrophy

Was half carried to the front seat,

Where he lolled while

Andy sat in the back.

Scenarios played themselves out in my writer’s head,

So I approached with some trepidation

A huge bristled Scotsman kilted to the brim,

Who stood crying, and in between sobs and the rush of air,

Related a narrative of sorts. . .

“Been living together. . . they used to watch my bairns.

Fishing trips. . . sweetest man. . . the two of them,

Living as one, not married, oh no,

But one still daft aboot the other,

When he comes down with the limb girdled curse.

So’s things worsen,

And he gets bit by what’s drivin’

The brethren in there,

Never had time for it myself.

Plus there was matters of money,

Gettin’ married so the State don’t

Scarf up the leavin’s.”

I think the worse: Marriage of convenience.

Separate vacations; a lover on the side.

Patience running thin.

How long can this last?

Two years later we return to St. Ives,

Older, slower, cliff wary, joint weary,

And on the spur, Sunday morn,

We make our way into Fore Street Methodist

As the Congregation Sings,

“Nearer My God to Thee”.

On the right, across the aisle,

Sit Andy and Reggie.

Sit isn’t an apt description,

For a quiet but continuous frenzy ensues.

As his hands become gnarled, she soothes them out,

She turns his head, lifts his hands in a mute praise,

And with a cup gathers saliva.

She catches me watching,

Her eyes reading, “steady on” no desperation,

No pleas for justice or put-uponness,

Just a resignation to thirty second ministrations

That will never end until. . .

During the sermon they left the service,

Doing a strange broken dance as she walked

Backwards holding his hands,

Opening doors and dancing thru.

A pause, then back again to sit,

But the dance will never end.

The Minister was preaching from the Gospel of John,

Of a time before the Messiah’s death,

When he knelt and washed his disciples feet.

“I have set you an example, that you should do as I have done for you.”

And across the aisle it was being done.

As hands were smoothed,

Neck gently rubbed, arms lifted for the release of breath.

Communion would round out the service.

Andy broke off a piece of bread,

And held the small plastic cup of juice,

Serving her mate, the body and the blood,

A liturgy in and unto itself,

As He would have us do for one another.

I became more aware then of the woman at my side,

Fifty years my companion,

And wondered if I too would kneel and serve,

And do a dance with her, one breath,

Together, until the temporal exigencies,

The husks that awkwardly encapsulate our Spirits,

Turn to dust and swirl towards the light eternal.

So thank you Andy and Reggie,

For the Word become flesh

For the reminder that a tremor

Or a breath from the one we love,

Are worthy of our lasting attention,

And that you allow us to catch a brief glimpse of

The Christ Within.